POST WRITTEN BY: Maria Dollas (’16), J.D. Pace Law School

Often, there are no witnesses to a crime other than the victim. Given the stress and state of the victim the question arises whether such conditions affect this lone witness’s ability to accurately recall the assailant. Things become more muddied when the police apprehend an assailant (not necessarily THE assailant who committed the crime in question) and the police proceed to do more than to merely present the alleged assailant to the victim.

In a 3-1 majority the Appellate Division Second Department recently held that the use of showup identification by police was unduly suggestive and that the victim’s identification testimony should have been suppressed. People v. James, ___ N.Y.S.3d ___ 2015 N.Y. Slip Op. 03864 (App. Div. 2d Dep’t May 6, 2015).

The discrepancy in the attributes of the person the victim described and the person actually caught were significant: they varied in age, height, and attire. The victim described her assailant as about 20 years old, 6 feet tall, wearing a brown and white striped shirt. The person apprehended by police was 13 years older and 4 inches shorter. A striped shirt of a different color combination, in this case a red-and-blue striped shirt was found near a parked vehicle and not on his person. Nonetheless, the police presented the person apprehended in handcuffs to the victim. That alone might have signaled guilt. It was particularly suspicious since the person arrested was walking shirtless in the area.

Still, the victim was not able to identify her assailant. It was only when the police purposely placed the miscolored striped shirt across the defendant’s chest that that the victim conceded that he was her assailant. The victim did not request the shirt to be placed upon the apprehended individual. Initially, she could not and did not identify him. It was only after the police officer took active steps that the victim said he was the one.

There is no doubt that the crime was committed. There is however doubt as to the reasonableness of the police tactics in presenting the apprehended individual to the victim. Showups and other identification procedures are not to be so unduly suggestive as to violate due process. The primary evil to be avoided is a “very substantial likelihood of irreparable misidentification.” Simmons v. United States, 390 U.S. 377, 384 (1968).

The law is not concerned with the number of witnesses but rather with the quality of the identification given. Even a slight deviation from permitting the victim to objectively determine whether the person presented to her as the assailant taints the process. The circumstances in this case are not free from coaxing the victim even so slightly as to whether the right shirt and therefore the right person is in custody.

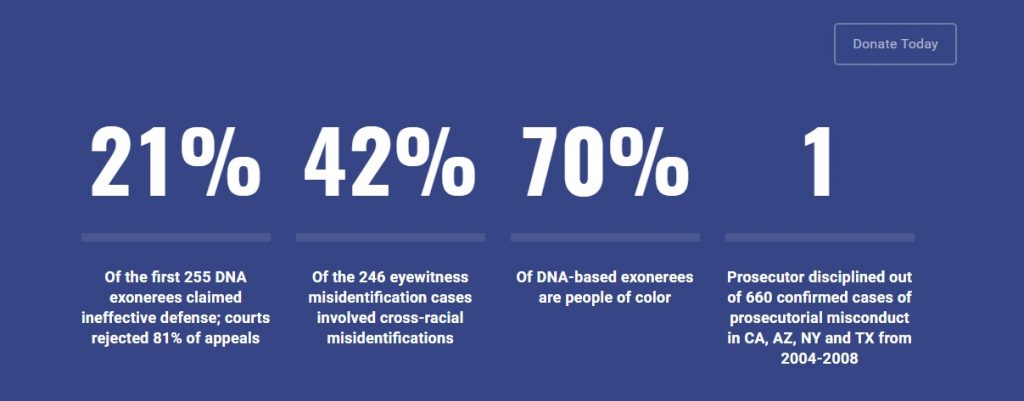

Additionally, the identification here may have been a cross-racial one: the assailant was described as a light skinned black male, the victim was only described as a 22 year old female and her skin color was not noted. Ordinary human experience indicates that some people have greater difficulty in identifying members of a different race than they do in identifying members of their own race. See Gary L. Wells & Elizabth A. Olson, The Other-Race Effect in Eyewitness Identification: What Do We Do About It?, 7 Psychol., Pub. Pol’y & L. 230 (2001). Here, an already challenging identification may have been even more problematic by irresponsible police tactics.

The people’s burden is not only to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that a crime was committed but justice requires that the defendant is indeed the person who committed the crime. One person wrongly identified is one person too many whose liberty and life may be irrevocably altered because of the procedural missteps of others. Misidentification and its consequences can also happen to you and me.

Related Readings:

- Andrew Denney, New Trial Ordered for Judge’s Failure to Suppress ‘Showup’ Identification Evidence in Robbery, NYLJ 1 (May 14, 2015) (access requires subscription to NYLJ).

- People v. James, ___ N.Y.S.3d ___ 2015 N.Y. Slip Op. 03864 (App. Div. 2d Dep’t May 6, 2015).

- Gary L. Wells & Elizabth A. Olson, The Other-Race Effect in Eyewitness Identification: What Do We Do About It?, 7 Psychol., Pub. Pol’y & L. 230 (2001).

- Simmons v. United States, 390 U.S. 377, 384 (1968).